Nouvelles

The true value of Montreal’s Olympic Park

Publié le 20 September 2018

Much has been said and written about the Olympic Park since the Games of the XXI Olympiad were held in Montréal 42 years ago.

Then Mayor Jean Drapeau had defiantly pronounced “It is no more possible for the Montréal Olympics to lose money than it is for a man to get pregnant.” In 1969, the City of Montréal set an initial budget of $120M to host the Games, later adjusting it to $320M in 1972. By February 1975, the figure had reached $610M, and five months later, $730M. Sadly, none of these estimates held, and the Montréal Games proved to be among the most expensive in the history of modern Olympics.

These cost overruns received extensive coverage and were scrutinized in the Commission of Inquiry into the Cost of the 21st Olympiad, presided over by Superior Court Judge Albert H. Malouf, in 1980. revealed that this enormous project had all the makings of a perfect storm: no overall budget, no project oversight, labour strikes, corruption, fraud, as well as the first oil shock in 1971, causing a sharp rise in the cost of raw materials.

On the heels of an article by journalist Michel Girard published in the Journal de Montréal about the costs of the Olympic Stadium, the Régie des installations olympiques (RIO) undertook an accounting exercise to establish the current value of its facilities in 2018. Here are the results of their research:

1972 to 1976 – Construction of the Stadium

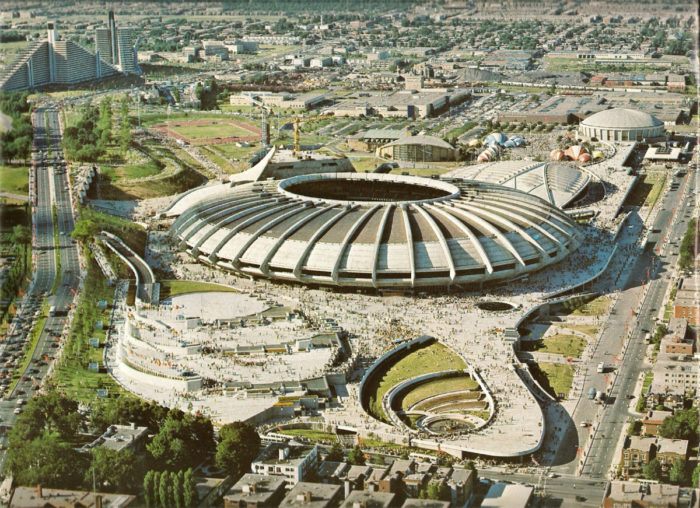

According to RIO data from October 31, 1976, the Olympic Park cost $937M. This figure includes the construction of the Velodrome, the Sports Centre swimming pools, 4,000 indoor parking spaces, the Olympic Village and the Sherbrooke viaduct. As we know, the Stadium was not fully completed at that time, the Tower was unfinished and the structure had no roof.

1977 to 2008 – Completion and transfer of ownership

Between 1977 and 2008, the RIO pursued the Olympic Park’s construction and maintained its facilities. During this period, spanning 31 years, a number of events punctuated the Park’s history:

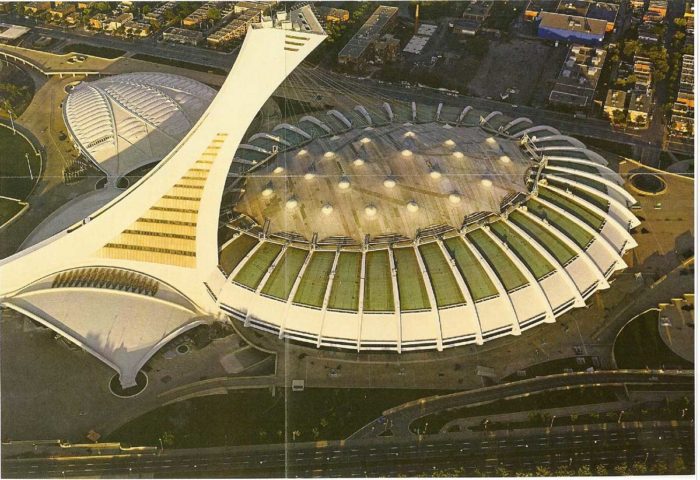

- Completion of the Tower in 1987 and installation of the initial roof, made of Kevlar, and of the second roof, a fixed, flexible roof by Birdair that remains on the Olympic Stadium to this day.

- In 1992, the Velodrome was transferred to the City of Montréal as part of its 350th anniversary celebrations and $50M in public funds was injected to transform it into the Biodôme.

- The Olympic Village was sold in 1998 for $62M.

- The RIO continued to ensure the upkeep of its facilities.

During this period, the municipal and provincial governments invested a total of $540M in the Olympic Park.

2009 to today – A landmark is reborn

In 2009, the incumbent government decided to reinvest in public infrastructure to address the maintenance deficit that had accumulated over the previous years. Government organizations with property assets in trust, like the RIO, seized this opportunity to establish capital plans for pursuing infrastructure maintenance. The Olympic Park also set up an equipment maintenance plan using the capital funding envelope provided by the Québec government. In the last few years, this plan has resulted in major construction and renovation projects, including the construction of the Institut national du sport du Québec, renovations at the Sports Centre, repairs to the thermal power plant, upgrades to the Montréal Tower and the arrival of Desjardins Group as a tenant. Many other current and future projects are under development as well. In total, between 2009 and 2017, $279M was spent on maintenance and new projects at the Olympic Park.

For these three periods, the total figure for Olympic Park construction and maintenance—all levels of government combined—is $1.7B. This amount, indexed to the 2017 consumer price index, amounts to $5.2B.

As such, the east end of Montréal is home to a very significant public asset, and has been for 42 years. Elected officials at the time had wanted to develop a unique urban park for future generations—a creation that would be the envy of all. We also now know, thanks in part to the Docomomo Québec heritage study, that the site chosen for this monument of modern architecture was no coincidence, and that Montréal’s plans to host the Games date back almost a century to when the city first submitted a bid for the Winter Games in 1928. It took 40 years and five unsuccessful attempts (1928, 1938, 1944, 1956, 1972) for Montréal to host the Games.

The future of the Olympic Park is promising. Close to $1B in investments are earmarked for the Olympic District in the coming years, from all levels of government combined, as illustrated by this map posted on the Olympic Park website. Within less than 10 years, this district will be a huge, one-of-a-kind and highly coveted urban park representing the legacy that our generation will pass onto the next, as our parents and grandparents did for us.